On April 23, 2020, a paper titled A Model of Cascading Change: Orchestrating Planned and Emergent Change to Ensure Employee Participation was published in the Journal of Change Management.

In it, the authors, Kasper Edwards (Technical University of Denmark), Thim Prætorius (Aalborg University Copenhagen), and Anders Paarup Nielsen (Technical University of Denmark), describe a fascinating fusion of planned change and emergent change (often seen through the lens of top-down and bottom-up, respectively) that led to a successful change management project within a leading cardiology department in Denmark.

The Model of Cascading Change has, according to the authors, three “enabling change drivers.” These include:

- A cascading change process with structured, transparent handovers

- A Lewinian-inspired process that cascades across organizational levels

- An orchestrated change process whereby management sets the direction, but staff generates a list of challenges and proposed solutions

Change context

This change management project arose due to the challenges resulting from a 2011 merger (the thorax surgical clinic and the anesthesiology clinic from a nearby hospital merged with and moved to the cardiology department) that caused a staff increase of 40%. The merger took place without any significant work to integrate the two departments at operational or personnel levels. A year later, tensions were rising. Management and staff both believed productivity had declined, and staff reported a decreased sense of wellbeing.

In January of the following year, the cardiology department management team initiated a change process by inviting a lean consultant and an external research consultant (author and interviewee Kasper Edwards) to determine the best way forward. By the spring of 2015, 29 of the 31 areas for improvement were successfully achieved (the other two remained outstanding due to budget reasons).

Questions for Dr. Kasper Edwards

CC: The paper states that “organizational change literature routinely attributes organizational change success to one of two contrasting perspectives.” We’ve known, at least since Wanda Orlikowski’s work (Improvising Organizational Transformation Over Time: A Situated Change Perspective, 1996), that it’s essential to integrate both.

Why has the field of change management held so tightly to separating the two (planned change vs. emergent change) rather than embracing their necessary interconnections?

KE: I can only speculate: The two approaches are distinctly different and require a similarly different mindset and management approach. In addition to the combined approach demanding a different mindset, one barrier could be timing.

In practice, change managers must display strict discipline to ensure each type of change is considered on an ongoing basis and at different intensities at various points in time.

In our case, we were two consultants that sparred and coached the top management team (TMT) during the process.

CC: Let’s dive into the case. You get the call from the cardiology department. They need help. Can you walk us through how you parsed through the many change management frameworks and peer-reviewed journal articles to assemble what you believed would be the best way forward for the department’s challenges?

KE: The process was more of a design and dialogue with the cardiology department. Initially, they framed the project as a straight lean project with added work environment perspectives. However, the different views within the management made it difficult to identify causes and a universally accepted project design.

Consequently, we proposed a diagnostic phase and postponed decisions on actual methods and goals. The idea of diagnostics was accepted by the management and led to the Effect Modifier Assessment (EMA) workshops, diary, and observation.

When we realized the lack of trust in management, it immediately became clear that a top-down process was out of the question and that intensive employee participation was necessary to get buy-in.

CC: What factors led to the situation you walked into — of the staff generally feeling opposed to the management? To what extent, in your opinion, did this opposition exist before the merger? Post-merger, did the two staff groups feel aligned in their opposition? Lastly, how could this opposition have been mitigated in the early stages of the merger?

KE: The lack of trust between managing and staff was preexisting. The merger accentuated the perception of management not being actively involved.

The two groups had similar perceptions regarding management. It was not necessarily an opposition but a lack of trust and belief that management would keep their word.

The merger could have been an arena and an opportunity to show leadership. In practical terms, management should have actively onboarded the new group and facilitated integration.

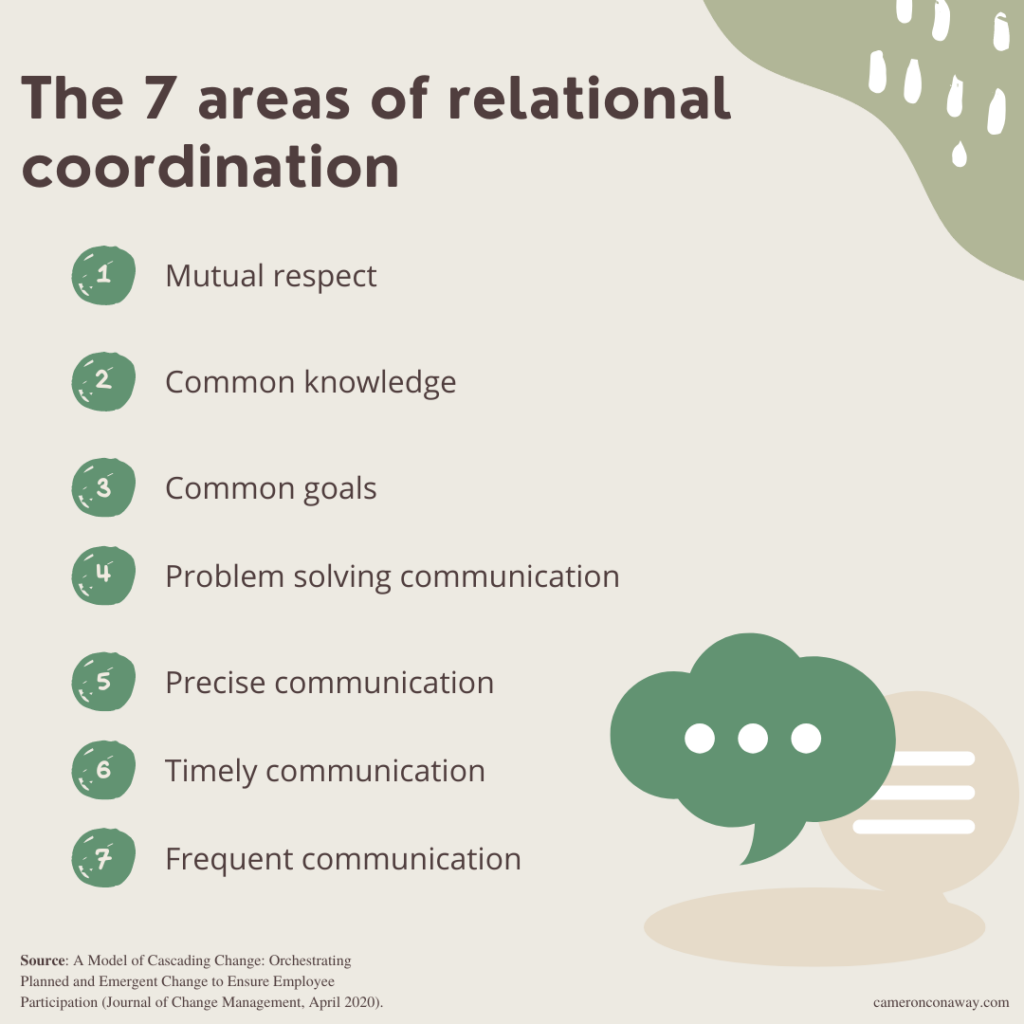

CC: You mapped out seven areas of relational coordination:

- Mutual respect

- Common knowledge

- Common goals

- Problem solving communication

- Precise communication

- Timely communication

- Frequent communication

While all seven improved after the project, I’m most interested in how the four areas of communication improved.

What did these types of communication look like before the change, and what key elements led to all parties seeing the improvement?

KE: Relational coordination and process development are two sides of the same coin. When the processes are commonly known, the people in the processes understand what to expect from each other. Communication, therefore, often becomes more precise, timely, and frequent.

A concrete example was the agreement on when to call the surgeon. Before the project, many different approaches existed. This led to frustration and needless discussions.

Problem solving communication, for example, was part of the collaboration theme, e.g., the improvement suggestions were shaped around improving collaboration and reducing ineffective behaviors.

CC: Understanding the pre-change situation was critical to the success of this project. It at once gave you a sense of the organization’s design while paying homage to the history and capturing present-day challenges. The model you used contained three parts: a kind of anthropological observation of the end-to-end process of procedures, workshops designed to bring out history, and written diaries.

How did this process come about? What, if anything, would you have changed about it now that you are a few years removed?

KE: Even now, a few years later, I would do the same general process.

Improvements would be more observation of surgery and daily practice. Such observations lend credibility to discussions in workshops. I frequently used my observations as examples during both the EMA and A3 workshops [an approach to problem-solving based on continuous improvement concepts popularized at Toyota].

The results of the EMA workshops could have also been further developed. Since then, I developed the EMA method to quantify and group events into themes more stringently and transparently than we did during the change management project.

CC: By May 2013, the project now had a name. As we discussed earlier, communication improved by just about every measure. Take us back to the basics.

When you determined the need to send that all-staff email, how did you decide its scope and shape? What responses did it generate?

KE: As the TMT and us consultants realized that a tightly controlled approach was needed due to lack of trust, we discussed how to communicate. The TMT, in addition to serving as managers, represented the different medical specialties. It was agreed that the TMT should act as one unit and communicate as one unit.

Scope and shape were discussed in the TMT, and it was deemed important to keep it short, i.e., one-page maximum. Because of the trust issues, the email had to be very clear in both wording and what was going to happen so it would help build trust.

The initial response was a cautious “ok,” illustrating that the email represented a new direction from the TMT and that the staff thought: “Sure… let’s see if you can pull this through.”

I believe the staff generally did not think the project would be completed, that it would be another organizational change roar with no bite.

CC: Let’s talk about the design of the six-step workshops. How did you determine the general structure and overall execution, especially considering that you were also working with an internal lean consultant?

KE: I have previously worked with Lean and A3 workshops, and I like the format. We did not change much on the A3 workshop design. Our primary consideration was the onboarding process.

As we had full surgical teams, there was a danger that medical doctors would dominate and ruin the workshops. This was accentuated by the bullying issues and meant we were very attentive to negative behavioral cues and openly addressed situations where comments approached personal boundaries.

Part of the onboarding was a Whole Brain-type test, which we used only to demonstrate that the participants represented different types of reasoning and that all were equally necessary.

CC: Patience had a lot to do with the success of this change management strategy. As I see it, the patience of the managers led to greater participation, which ultimately led to the foundation for a co-created change management process.

How did you see patience either being questioned or built across the change? What role did you as an external consultant play in this?

KE: Patience was indeed essential. The TMT was used to acting and being decisive. These behaviors were challenged in this change management project. I believe that the TMT accepted the diagnostic phase because it tapped into their medical mindset; it made sense to them to diagnose before administering a treatment.

The need for patience was questioned, especially at the start of the process. There was an urgent need to fix the problems in the department. However, as the results from observations, diaries, and EMA workshops began to emerge, there was an increasing trust in the process.

Interestingly, at this point, patience/impatience was more of a frustration that arose from not being directly involved in the activities. They gave up a bit of their traditional mode of control — keeping a firm grip on the overall leadership — and they had to come to terms with this.

—

*End*

Keep Learning

-> Read the most comprehensive change management definition on the web

-> Watch the most comprehensive feedback definition video