Summary. Employee feedback literacy is your capacity to effectively seek, give, receive, process, and use feedback — think having a challenging conversation with a direct report whose performance is pulling your team down (giving), learning from audience survey results that the presentation you spent months preparing didn’t land well (receiving), or working diligently to integrate that audience’s feedback the next time you take the stage (processing). Developing feedback literacy across teams can ensure a shared understanding of what feedback is, ease the stress that feedback can cause both givers and receivers, and ultimately help all workers become the learners and teachers they need to be for each other in a rapidly changing work environment. Unfortunately, holistic feedback training is rarely provided to employees; instead, if any feedback training is offered at all, it typically splits employees into camps: Individual contributors learn how to receive feedback while people managers learn how to give it. But when these camps are dismantled, so too are the invisible hierarchical barriers that can stifle learning cultures.

Published: November 1, 2023

In the morning, you saw the smiles of your colleagues and many heart emojis on your screen as you virtually presented quarterly results to your global team. In the afternoon, you receive a note from a regional manager who felt their territory wasn’t given the time it deserved in your presentation. That evening, to power through getting some extra work done, you have a cup of coffee a bit later than usual — and you struggle to sleep at night because of it.

In her book, Feedback Fundamentals and Evidence-Based Practices, industrial psychologist Dr. Brodie Riordan refers to these types of moments as “feedback events” and she leads the reader through an inventory of 25 she captured just on a typical day in her life. Dr. Riordan’s point was to challenge our idea of feedback as primarily what happens during the quarterly performance review by showing us that feedback is literally all around us. Once we bring awareness to the ubiquitous nature of feedback, we begin to see its stunning dimensionality and modes of expression — how it includes not only the traditional manager-to-employee direct feedback relationship but also the subtle non-verbal gesture of your colleague, the self-reflective feedback that arises from observational learning as you compare your performance next to the performance of someone you admire, and even the wisdom of your body as your sympathetic nervous kicks in to try to protect you when you’re stressed.

There is perhaps no greater mechanism than feedback to catapult our personal and professional development. But it’s complex. Sure, if we see feedback not in all its multidimensional splendor but in the myopic view of simply other biased people pointing out what they see as our perceived flaws, then, yes, we enter into the feedback fallacy realm. In the workplace, the dearth of comprehensive feedback training for all employees suggests two assumptions we haven’t yet broken free from: that developing the organization-wide skills to effectively give, receive, and process feedback is a nice-to-have but not a critical business imperative, and that it doesn’t require investment because we’re all already good enough at it.

Good Enough Isn’t Enough

According to one study, 44% of managers said they find it stressful to give negative feedback, 21% avoid giving it at all, and a whopping 37% said they even avoid giving positive feedback – which decades of research suggests has a tremendous impact on employee satisfaction. These numbers are especially troubling for two reasons: Employee development starts with managers and it’s clear that employees want feedback and know how important it is for their career development.

When I first began providing employee feedback literacy training, I sat across from Khai*, who was about to become a first-time people manager on a newly formed team. Khai courageously admitted feeling scared to give feedback to their new teammates, then rattled off a range of great questions, including: “Before giving feedback, should I spend a few months getting to know my team so that we first have a strong rapport?” and “Should I only give feedback on areas within my subject matter expertise?”

For Khai, moving into a people manager role meant they had to rapidly understand what it was like on the other side of the feedback line. I learned that Khai’s apprehensions were born out of the challenging workplace culture they were leaving behind. In their previous job, they hadn’t had a healthy feedback culture modeled for them, one in which everybody on the team, regardless of title, felt psychologically safe and had the skills to give and receive feedback effectively. In essence, rather than tap the wisdom of individuals to form a continuously-learning collective genius, Khai’s team was assembled into one large group of passive feedback receivers (those who were perceived as knowing little and needing feedback all the time) and one very small group of feedback givers (those who were perceived as all-knowing givers) – neither of which had received any feedback training.

After many conversations with leaders from global companies, I’ve come to realize both how common and how unhelpful this grouping can be for developing a learning culture. The “good enough” assumption with feedback has a cascading effect, whereby passionate and promising future leaders like Khai grow into the kind of managers in the study who struggle with nearly all aspects of feedback.

So we have managers struggling to give it, employees wanting it, organizations not investing much in it, and educational psychologists like Dr. James McKenna highlighting that in increasingly volatile and competitive industries it’s a key to building a learning culture that can help organizational resiliency. Where to from here?

Enter Employee Feedback Literacy

As we covered in Feedback Literacy: A Framework for Educators, the concept of feedback literacy has roots in the world of education where it primarily focuses on students receiving and processing feedback. As I’ve brought the term into organizations by expanding the concept to include the capacity of all working people to effectively give, receive, and process feedback, something magical has happened: the dismantling of the invisible walls that too often separate groups of givers and receivers.

Managers at all levels are able to take a more holistic approach to developing their feedback capabilities; they see themselves not as purely feedback givers but as on the endless path to becoming more feedback literate, with “giving” as only one dimension. Individual contributors who once felt disempowered and merely passive recipients in the feedback process now understand the challenges their managers may have in giving them feedback and feel more confident in exhibiting feedback-seeking behavior, which we’ve known since the 1983 work of Ashford & Cummings can change feedback relationships for the better. And, perhaps most importantly, introducing feedback literacy creates a common language and a common ground for all employees to recognize that feedback is multidimensional and an ongoing developmental path that everybody is on.

Threading It Through Your Learning Culture

Whether you’ve consciously built it or not, you have a learning culture. And this culture is significantly impacted by the feedback literacy of individuals within it. For example, if teammates are afraid to provide feedback to each other – because they don’t quite know how or lack psychological safety, or both – vital knowledge will remain trapped within individuals rather than unleashed for the benefit of the team. In such cultures, I’ve also seen “shadow learning” taking place, whereby individuals secretly pursue all types of learning opportunities but feel the need to hide that they did it, which again keeps insights locked within the individual. If we take the classic metaphor of a team as an organism, you can imagine individual parts of the organism becoming stronger but the overall organism itself remaining no more resilient.

Fortunately, threading feedback literacy into your learning culture is in all of our hands. While I still recommend all employees receive formal feedback training, leaders can dramatically improve their learning culture by having feedback literacy-centered conversations with their teams (and encouraging all people managers to do the same). Below is a simple but effective three-step process for facilitating these much-needed conversations. I recommended breaking these into multiple meetings.

Co-create a feedback definition

Researchers Boud & Dawson write, “For feedback to operate well, all parties involved need to understand the common enterprise in which they are engaged and appreciate the ultimate purpose of the activity.” Few books and articles about workplace feedback actually provide a feedback definition, so it can be a great introductory exercise to co-create a unique definition for your team.

Be sure to state your why at this stage. Share how important you believe it is for everybody to feel safe to give and receive feedback. Let your team know that you want to receive their feedback, too, and that your goal is to create a healthy feedback culture, which you will need their help with. To make it real, share an experience of a time when you received feedback that was delivered well and contributed to your professional growth. You could say something like, “Early in my career, I once had a manager who would provide great feedback by framing it as ‘Here’s what worked for me when I was in a particular situation.’ Looking back, this framing helped reduce my anxiety and defensiveness, and it made me feel in control of my improvement rather than being mandated to do something.”

As you facilitate these conversations, you may find that folks have different ideas about what feedback means – and creating a safe place for these differences to be shared can help ensure all individuals feel part of what’s being built and that you ultimately get everyone on the same page regarding the purpose of feedback. In future conversations, you may find yourself referencing the definition your team came up with. As a starter, here is how I define it:

“Feedback is a response to a person’s activity with the purpose of helping them adjust to become more effective. Feedback comes in various forms, including evaluative (how you did and where you are), appreciative (how you are valued and recognized), and coaching (how you can improve).”

This definition is far from perfect, but I’ve received positive feedback about it and it’s helped me ensure all training participants have a shared understanding before we advance into more complex material. The three forms included in this definition come from the book Thanks for the Feedback by Harvard Law School faculty members Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen.

Introduce feedback literacy

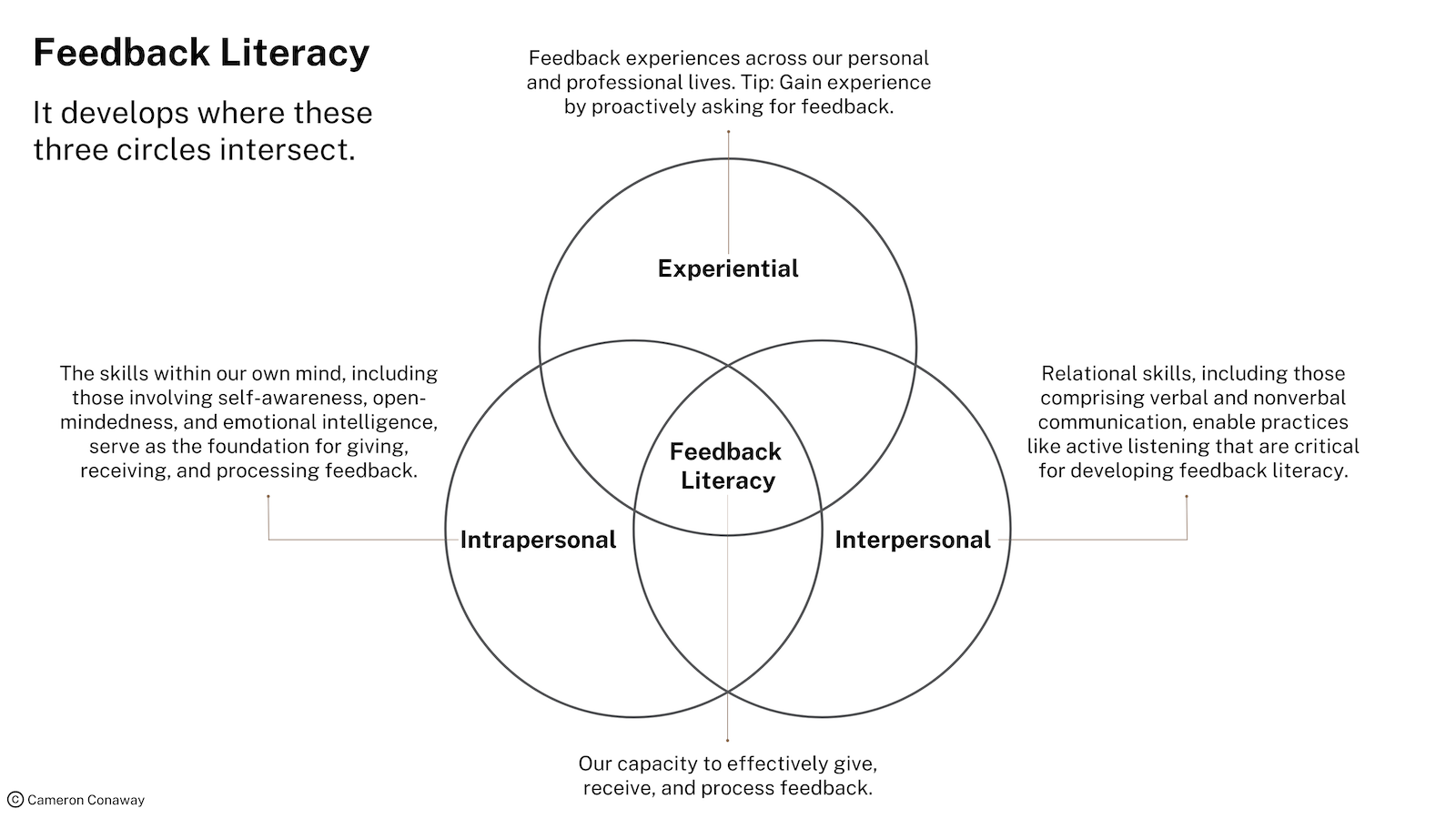

Many elements make up what we are describing as feedback literacy. I’ve found it helpful in conversations to have a visual to steer the conversation. Of course, there’s more than one way to show these relationships. But here is a simple model I created.

Each element holds its own space, but the dotted lines represent fluidity as each element can influence the other. Here is how it works, starting from the inside out:

- Feedback Literacy: Feedback literacy is at the core because, although developing it takes being in relationship with others, it is an individual capacity we can develop. Extending from this core individual capacity are the specific skills in being able to give, receive, process, and generally experience feedback. All of this extends into the enclosed outer layer of the feedback culture.

- Experiencing, Receiving, Processing, Giving: With a named element now describing the core component of feedback, all employees can see the relationships between the many other feedback elements. It’s easier to discuss and develop the ability to process feedback, for example, when everybody can see it represented as a skill within a larger model.

- Culture: Although it influences and is influenced by the other parts, Culture encloses all elements and is both an expression of and a contributor to a group’s feedback literacy. When managers receive advice to build a healthy feedback culture, they can now see this means recognizing existing elements of the culture that may not be helpful and modeling and otherwise helping their team develop the skills that feed into feedback literacy.

Co-create an employee feedback literacy development plan

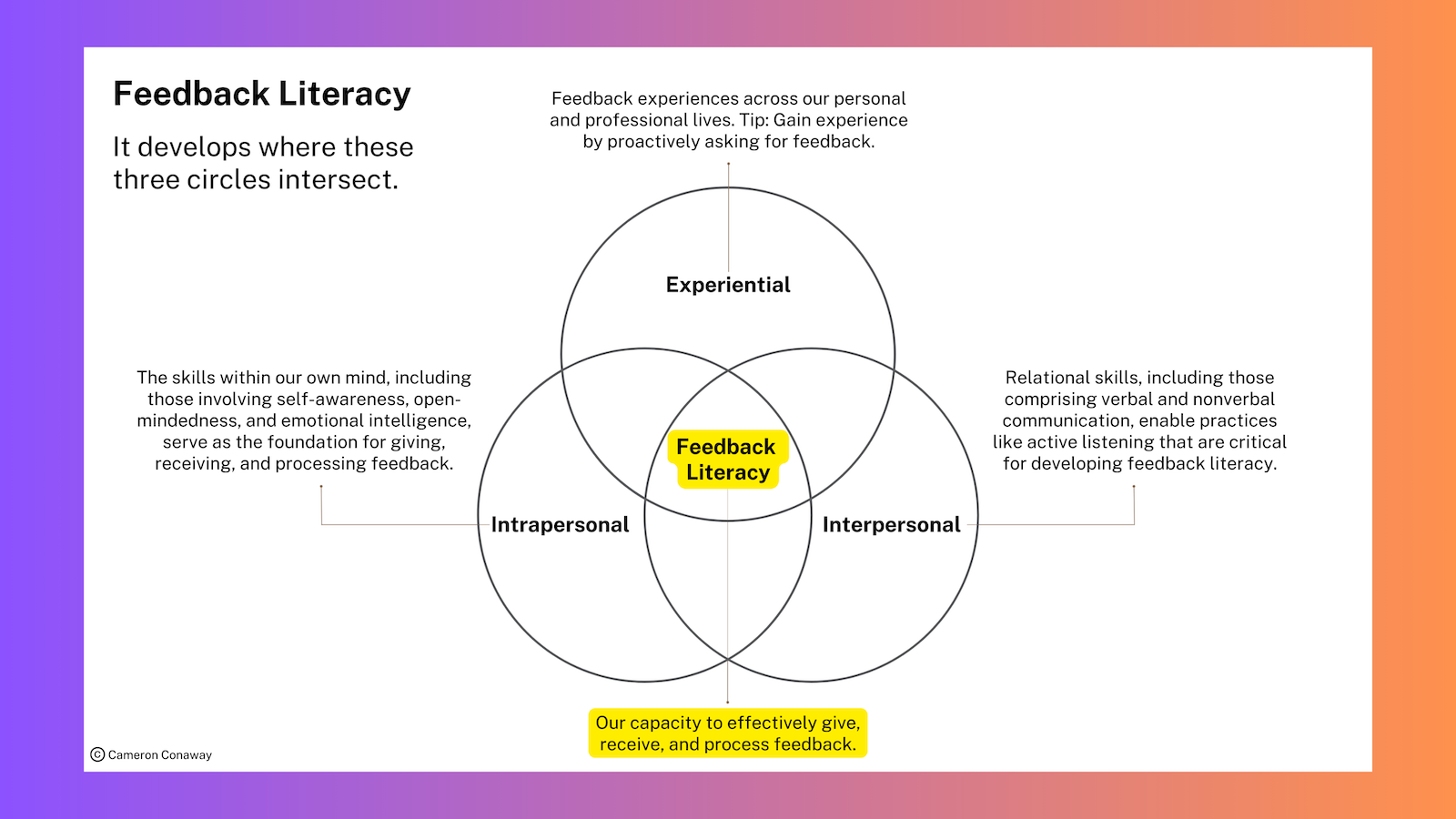

Through conversation, leaders can create an individualized approach to help employees begin building their feedback literacy. Getting it into a development plan is important for integrating learning into each employee’s workflow. As with introducing the concept of feedback literacy, I’ve found it helpful to visualize what I see as the three primary developmental areas of feedback literacy. I’ve also found it helpful to provide a brief glimpse into what each area means and then allow the individual to take it to the next level regarding how it might apply to their development.

- Experiential: Feedback literacy develops through the full range of feedback experiences across our personal and professional lives. One way to gain experience, especially in a feedback-averse culture, is by proactively asking for it. This will allow you to see and learn from different feedback delivery styles and practice how you receive and process each. As with developing any other type of literacy, experiential practice is vital. Only through intentional practice can you see, for example, that your default reaction has always been to get overly defensive upon receiving even relatively minor negative feedback. With this new awareness, you can develop more skillful means – such as perhaps taking a few deep breaths to calm yourself – when you notice the defensiveness arising.

- Intrapersonal: Self-awareness and self-reflection are two of the many dimensions of intrapersonal skills, and they are critical for developing feedback literacy. For example, improving your ability to recognize and be with (rather than respond to) your own emotions will help keep you receptive and grounded during challenging feedback conversations. And, for some, positive feedback may actually be more challenging than negative feedback. This can occur for several reasons, including because they may have built a certain level of comfort with negative feedback due to the intensity of it arising in their own inner monologues. Ways to improve self-awareness and self-reflection can include meditation, journaling, working with a licensed therapist, and working with a career coach.

- Interpersonal: Relational skills, including those comprising verbal and nonverbal communication, enable practices like active listening that are critical for developing feedback literacy. Employees can develop interpersonal skills by setting specific goals for the aspects they want to improve and then consciously observing and learning from others, requesting feedback about their interactions, and watching and learning from recordings of their performance.

Organizational Learning via Employee Feedback Literacy

The need for organizations to invest in nurturing their learning cultures will become more important, but they must not think it begins and ends with helping individuals acquire new technical skills. While this individual re-skilling and up-skilling will be vital, what will make or break an organization will be not in how they equip individuals but in how they equip teams to continuously bring forth their collective wisdom.

Ultimately, organizations will be in a far better position to manage change when their teams, like the murmuration of birds, can learn and adapt together in real-time. To get there, all employees must have a chance to remove learning barriers by developing their feedback literacy.

***

*Name changed to protect identity

See also: 3 Barriers to Effective Feedback at Work (and How to Address Them)